Looking at the Masters: Miriam Schapiro by Beverly Hall Smith

Miriam Schapiro was born in 1923 in Toronto, Canada, to Russian Jewish parents, but she was brought up in Brooklyn, New York. One of her grandfathers was a rabbi and the inventor of the first moveable eyeball for dolls. His invention was used in the manufacture of “Teddy Bears” in the United States. Her father was an artist and industrial designer; her mother was a homemaker. Both parents encouraged Miriam to make art, and by age six she was well on her way. She earned a BA at the State University of Iowa in 1945, an MA in 1946, and an MFA in printmaking in 1949.

During her college years, Shapiro met and married Paul Brach (1924-2007), also a Jew and an artist. During his service in the armed forces, Brach witnessed the horrors of the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp in Czechoslovakia after it was liberated by the Russians in 1945. Schapiro’s Russian Jewish heritage certainly had an impact on her art. Brach received a position as a painting instructor at the University of Missouri. Miriam did not.

Schapiro and Brach moved in 1951 to New York City where they met the Abstract Expressionists, rising stars of the art world. She was not included in the group since women were not considered serious artists. She worked at the Parsons School of Design to earn money to pay for her son’s daycare in order to find time to paint. Her new paintings were large, like those of the men, and abstract with broad gestural brush strokes. The paintings were based on black and white photographs of the paintings of the Old Masters. Andre Emmerich selected one of her paintings for the inaugural exhibition at his new gallery in 1957.

Schapiro’s career began when she and Brach moved to California. She and Judy Chicago were employed in 1971 by the California Institute of Art in Valencia to establish the first Feminist Art Program. Woman House was an entire house given to the women. Each room was designed to reflect what women felt they needed to be and to do there. An entire book records the rooms and events that happened there. The results were outstanding. Schapiro’s work was developing in a new direction. She wrote in 1974, “I began to see myself as another kind of artist, as a woman artist, very much connected to those women who had made quilts, who had made samplers, who had done all of that women’s work throughout civilization, who are not honored, but whom I honor, and I honor them by continuing their tradition. The difference is that I don’t work with sewing; I’m a painter and I work on canvas, and I work in their tradition.”

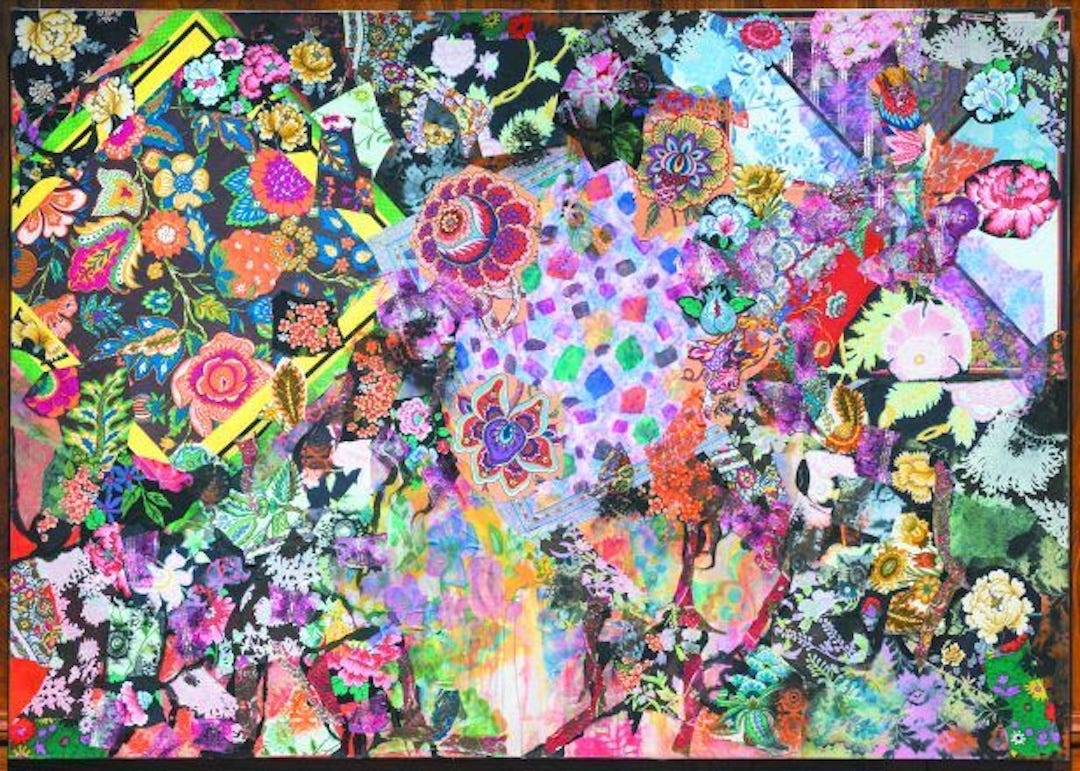

“The Beauty of Summer” (1973-74)

Shapiro began to study the role of women in art over time. She created mixed media art with paint and fabric, quilting, embroidery, applique, lace, ribbons, photographs, even the color pink. The works would have in her words a “woman-like context” that “celebrates a private and public event.” “The Beauty of Summer” (1973-74) is an early collage that celebrates Summer. Flowers abound, and the garden is full, overflowing with joy. It is feminist and unique, and it is engaging.

She was a major force in the Women’s Movement along with Betty Friedan, Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and others. The National Organization of Women (NOW) was created, and the College Art Associations authorized the Women’s Caucus for Art (WCA), both in 1972.

She challenged the existing male dominated concept of high art and low art by creating what she called Pattern and Decorative Arts. She called the works femmage, inspired by the “art out of women’s lives” and intended to validate “the traditional activities of women.”

“Anonymous was a Woman” (1976)

Schapiro began with collages that paid tribute to such women as Impressionists Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. She began her first Collaborative Series, working with nine women who were studio art graduates of the University of Oregon. The group was a reflection of the traditional collaboration among women to make quilts and lace. Each “Anonymous was a Woman” (1976) (30”x22”) (series of nine) was begun with an etched print of a hand-made doily.

She was invited to lecture in several states, and she collected samples of items from women who attended. She and fellow artist Melissa Meyer wrote and published “Waste Not Want Not: An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled” (1977-78) that listed assemblage, decoupage, photomontage, “traditional women’s techniques–sewing, piercing, hooking, cutting, appliqueing, cooking and the like….”

“Barcelona Fan” (1979)

“Barcelona Fan” (1979) (72’’x12’) was inspired by the traditional hand-held fan. Schapiro said the fan “reveal[s] the unfolding of woman’s consciousness,” serving as “an appropriate symbol for all my feelings and experiences about the women’s movement. That’s a very ambitious notion: to choose something considered trivial in the culture and make it into a heroic form.” At 12 feet across, the piece embraced the practice of men making large works.

Fans have found their uses over time in many cultures. Women in the 19th Century used their fans to engage in discreet communication. The fan is an important element in flamenco dancing. Dancing was one of Schapiro’s passions. Areas of paint, fabric, and lace create a colorful and bold pattern divided into 24 radial sections, the whole divided into five semicircles.

“Barcelona Fan” (detail)

This detail of the outer semicircle provides a closer view of one of Schapiro’s iconic images.

Schapiro in her studio, ”Black Bolero Fan” (1980) behind her, and ”Azerbaijani Fan” in front

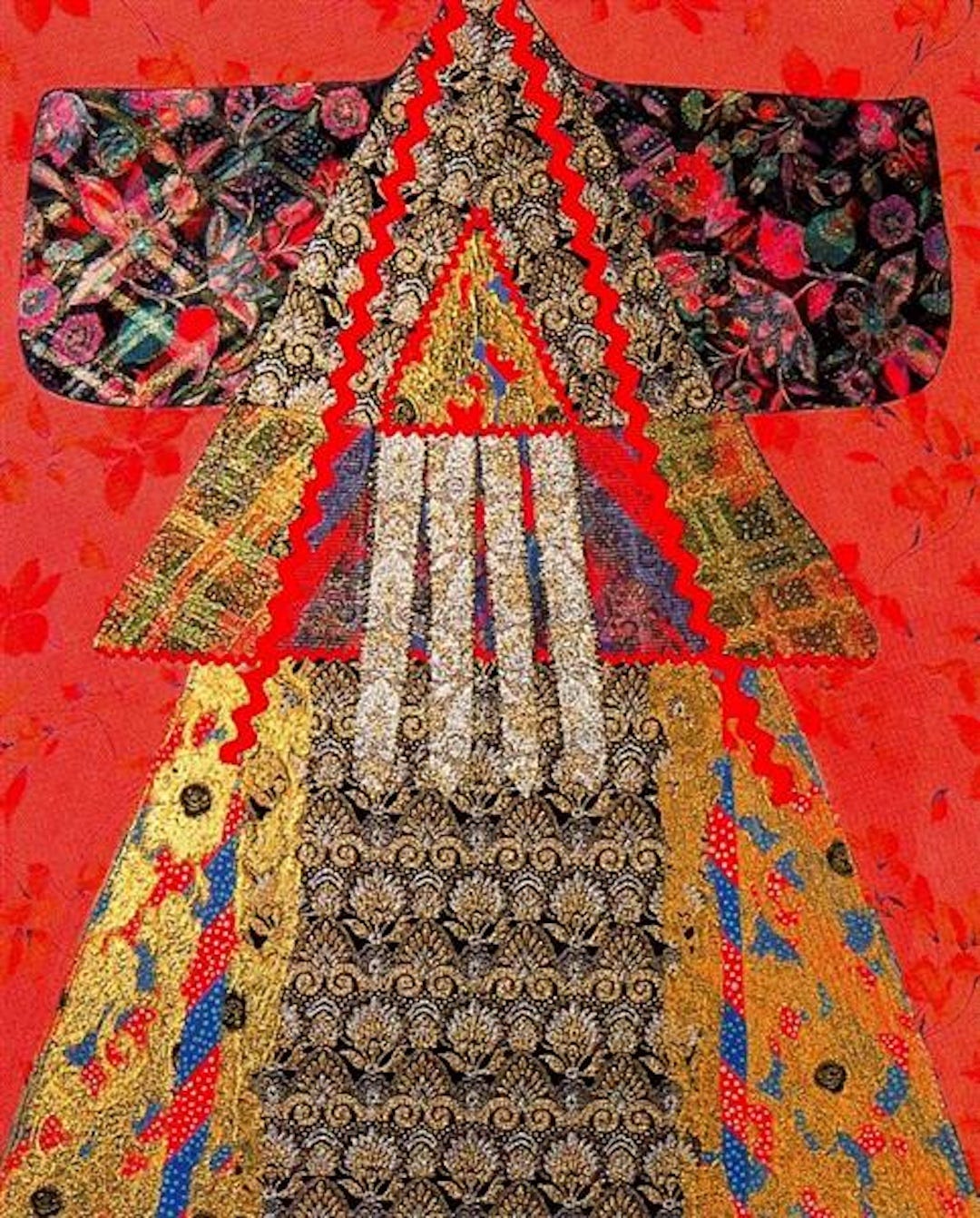

‘Golden Robe” (1979)

The fabrics and layered construction of Japanese kimonos fascinated Schapiro. “Lady Genji’s Maze” (1972) (not shown) was followed by “Anatomy of a Kimono” (1976) (52 feet long) (not shown) was followed by the Robes Series. “Golden Robe” (1979) is an example of the larger than life-sized collage of rich fabrics and distinct parts of a Japanese kimono. Schapiro’s kimono, fan, house, and heart-shaped canvases are among her iconic images.

“Four Matriarchs” (1983)

“Four Matriarchs” (1983) (80’’x30’’each) (acrylic) were designed for the Temple Shalom Community in Chicago. They represent the four Jewish heroines Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. The paintings were then made into stained glass windows for the Temple. Schapiro’s renewed interest in her Jewish roots also resulted in several works depicting Anne Frank and in particular Frida Kahlo, who referred to herself as Jewish, and with whom Schapiro identified as an artist. Each of Schapiro’s painted Matriarchs wears a brightly colored patterned garment and a unique hair style. They are linked together by semi-circle arm patterns. This design was commissioned to be made into stained glass.

Viewed in place, the Temple Shalom designs are brilliant. Schapiro’s strong interest in the patterns and colors of ancient Russian clothing come into play here. She has added to her depictions of women artists the Russian Avant Gard artists Popova, Goncharova, and Rozanova, and the French artist Sonia Delaunay. These women brought art into the modern age in the early 20th Century, alongside their male counterparts.

“I’m Dancin’ as Fast as I Can’’ (1984)

“I’m Dancin’ as Fast as I Can’’ (1984) is one of Schapiro’s autobiographical pieces. She worked hard to balance her various roles as a woman, mother, artist, historian of women in the arts, breadwinner, and challenger of male authority. When she was young, she took dance lessons, and her designs and patterns do have a sense of rhythm. She is the whirling dancer at the center of the composition, and the ballet dancer at the right side of the painting. Yet, a striding male figure leads the viewer out of the composition, leaving the women behind. He holds a cane and tips his hat. Miniature portraits of Goya and Van Gogh are included along with signatures of Rembrandt and Picasso on the blue back of his coat. The red, black, and yellow umbilical cord that links the ballet dancer to the whirling female is a personal statement

Schapiro danced as fast and as hard as she could, and among the many exhibitions and honors she received in her lifetime were four honorary doctorates and a Lifetime Achievement Award (2002) from the Women’s Caucus for Art.

“I talk about women’s traditional art, the art of women who decorated pots or did the weaving—the great Navajo weaving—the eye-dazzlers of the southwest. Most of the decorative art has been done by women throughout time and civilization. What happened long ago in art criticism was that a distinction was made between high art or fine art and low art or craft/decorative art. And all that craft/decorative/low art which needs a superb sense of color and design has been done primarily by women. So the patriarchal fix in criticism has always made that sexist distinction. What women did in the seventies was to reinvent pattern and decoration as an integral part of high art.” (Miriam Shapiro)

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown